Hole punching through NAT devices

- Goal of this blog post

- What is NAT and why do we need it?

- Simulate two clients behind NATs on a Linux machine

Goal of this blog post

I saw this very insightful video from Engineer Man in which he explains udp hole punching. I wanted to know more about it, and I to replicate his setup but without renting virtual machines from a cloud provider. This blog post will show how to replicate the video of Engineer Man on your own machine using virtual machines.

The thing I initially set out to study was whether I could identify conditions when hole punching works and when it fails. You can find an answer to this question on the internet, but I was not really satisfied with those answers, so I will present my own answer with detailed examples.

In this blog post you will learn:

- Conditions when hole punching does work

- Creating virtual machines with libvirt

- Configuring bridge networks with netplan

- Simulating machines behind different NAT’s (aka people on computers in their homes on their own WiFi)

- Firewalling and NATing with nftables (

nft)

You need to know:

- The command line basics

- The very basic of tcp, udp and ip

- Optional: it really helps to have some familiarity with networking concepts

You need to have:

- A system with Linux

- A CPU that allows for virtualization (relatively modern CPU’s support that)

Although the blog is written chronologically, lots of parts are useful by themselves as well. Please skip the stuff your are not interested in.

What is NAT and why do we need it?

NAT stands for network address translation, and for the rest of the blog I will use the word NAT to denote a device that does network address translation. In a typical home setup, the router that you got from your internet service provider (ISP) does network address translation. Why do we need a NAT? The internet still works mainly on ipv4 and there are only a limited number of ip addresses. To protect the number of ip addresses in the world we mostly operate behind NATs. You can have a lot of devices on your local network behind a NAT, but from the outside world traffic seems to come from the same ip address.

This is a reason why its very hard to convict someone for pirating copyright material, because its hard to determine which exact device did the downloading. This is also the reason you cannot sent tcp/ip packets directly to your grandma PC. You can send packets to your grandma’s public ip but you have no way of specifying to which actual device the packet should go to. Here is a picture with an example of two private networks behind NAT devices.

You could argue that having a NAT device as between you and the internet is a form of weak protection. One cannot send packets directly to you when you did not initiate contact first and it provides a weak form or anonymity: was it you or your roommate that downloaded that movie?

The main problem with devices behind NATs is: how do you initiate contact with another peer behind a NAT? One solution could be: client B configures his NAT in such a way that all traffic on port 80 gets forwarded to his device (this is called “port forwarding”). Then he has a program listening on port 80 for incoming traffic and handles it accordingly. Client A can send traffic to the public ip of client B to port 80, knowing that it will be forward to his device.

This solution works, but you have to configure port forwarding which is not very convenient and if client C (behind the same NAT as B) wants to talk to client A they have to negotiate another port number, because all incoming traffic on port 80 is being forwarded to client A already.

Another solution would be to have a service that acts as a relay between clients (for example Discord). This is less than ideal, because then you are dependent on a service to handle your communications properly. It would be nicer if communications could go directly from peer to peer. But how do you establish a peer to peer network connection when clients are behind NATs, that is where tcp or udp hole punching comes in.

Note: We would not need NAT if the world would switch to ipv6. There are enough ipv6 addresses to provide every machine with its own ip address. With no NAT you would lose the weak form of anonymity, but it would be easier to communicate peer to peer (in a secure way).

What is hole punching?

Normally, when a someone sends a packet to your public ip (that is meant for your device) your NAT device will drop the packet. Your NAT device will not drop the packet when it already expects a packet that is meant for you.

You can let your NAT know that it should expect a packet for you, by sending a packet yourself to the exact same address that you will be expecting a packet from. This creates an entry in the connection table of your NAT, and for a certain amount of time (120 seconds for example) your NAT will forward incoming packets to you (from the exact address that you send a packet to). If you will not get an answer in the set period of time the hole closes again, and you NAT will drop further packets.

So when client A and B behind NATs want to communicate peer to peer, they need to know:

- Client A and B need to know each others public ip addresses

- Client A should know the port number that Client B will be expecting traffic on

- Client B should know the port number that Client A will be expecting traffic on

- Either client A or B should punch a hole through their NAT so a connection can be established

This is a graphical representation how a packet would flow from client A to client B

Client A: (192.168.1.1, 23456, 89.43.234.116, 55555)

--->

NAT A: (77.123.456.111, 23456, 89.43.234.116, 55555)

|

internet

|

NAT B: (89.43.234.116, 55555, 77.123.456.111, 23456)

<---

Client B: (10.10.10.10, 55555, 192.168.1.1, 23456)

Definition of the tuple: (source ip, source port, destination ip, destination port)

Depending on the behavior of the NAT, hole punching will either almost always work, or almost always fail. Let’s go through an example of both.

An example when hole punching will almost always work

Let’s go through a tcp example when hole punching will almost always work:

- Client A sends a SYN to Public ip of client B:

(192.168.1.1, 23456, 89.43.234.116, 55555) - NAT A changes the source ip of the packet:

(77.123.456.111, 23456, 89.43.234.116, 55555) - Client A has punched a hole in NAT A. NAT A creates the following entry in its connection table:

120 TIME_WAIT SYN_SENT src=192.168.1.1 dst=89.43.234.116 sport=23456 dport=55555 [UNREPLIED] src=89.43.234.116 dst=77.123.456.111 sport=55555 dport=23456

this lines tells you a SYN packet has been sent, for 120 seconds your NAT device will wait for an answer packet with these characteristics (89.43.234.116, 55555, 77.123.456.111, 23456).

If a packet with these characteristics arrives NAT A will forward that packet to client A. If not the hole will be closed and NAT A won’t forward the packet.

- Client B sends a SYN to the public ip of client A:

(10.10.10.10, 55555, 192.168.1.1, 23456) - NAT B changes the source ip of the packet:

(89.43.234.116, 55555, 77.123.456.111, 23456) - The packet from client B will arrive at NAT A it matches the characteristics in the connection table of NAT A, NAT A forwards the packet the client A

- Client A and B will continue the tcp handshake

- After the handshake the entry in the connection table of NAT A will be:

431994 ESTABLISHED src=129.168.1.1 dst=89.43.234.116 sport=23456 dport=55555 src=89.43.234.116 dst=77.123.456.111 sport=55555 dport=23456 [ASSURED] mark=0 use=1

Which indicates the connection is established, and will be alive for 431994 seconds!

In this example 2 clients are behind NATs devices that do not change the port numbers: in this case hole punching will almost always work.

An example when hole punching will almost never work

In this example 2 clients are behind NAT devices and NAT B changes the source port number. In this case hole punching will almost never work

- Client A sends a SYN to Public ip of client B:

(192.168.1.1, 23456, 89.43.234.116, 55555) - NAT A changes the source ip of the packet:

(77.123.456.111, 23456, 89.43.234.116, 55555) - Client A has punched a hole in NAT A. NAT A creates the following entry in its connection table:

120 TIME_WAIT SYN_SENT src=192.168.1.1 dst=89.43.234.116 sport=23456 dport=55555 [UNREPLIED] src=89.43.234.116 dst=77.123.456.111 sport=55555 dport=23456

- Client B sends a SYN to the public ip of client A:

(10.10.10.10, 55555, 192.168.1.1, 23456) - NAT B changes the source ip and the source port of the packet:

(89.43.234.116, 49873, 77.123.456.111, 23456) - The packet from client B will arive at NAT A it does not match the correct characteristics because NAT B changed the source port, NAT A will drop the packet

- A connection cannot be established

So, when does hole punching work? When both NAT devices do not change the source port numbers of the outgoing packages! Why? If the NAT of client A changes the source port number, client B does not know where to send the traffic to. Also, client A punched a hole through its NAT but its expecting traffic from client B with a different source port number, so client A will drop the packet from client B. If one of the 2 NATs changes the source port number, hole punching will fail.

In the literature NATs that change source port numbers are called symmetric NATs.

Note When one of the two devices is not behind a NAT (even a NAT that changes source port numbers) no hole has to be punched and a connection can always be established (if there are no other firewalls of course).

Simulate two clients behind NATs on a Linux machine

In the rest of the blog post I will go on about how you can replicate 2 clients behind NATs on your own machine. So you can try hole punching yourself.

The basic idea is as follows:

- Simulate 2 bridge networks (2 virtual switches)

- On those 2 networks “plug in” 2 virtual machines (VM)

- Configure one VM to be a NAT (router) and configure one VM to be a client

I will cover:

- The creation of VMs with libvirt

- The configuration of bridge networks with netplan

- How to configure the VMs so they will use the bridge networks

- The configuration of the ip addresses and routes with

iproute2 - The configuration of a firewall for the client VMs with

nftables - The configuration the NAT VMs also with

nftables

Creating VMs with libvirt

Creating and working with VMs using libvirt is pretty convenient. If you want to know how to install VMs with libvirt check this blog from octetz.

I love how his blog starts, I feel the same way: … (with libvirt and linux tools in general) you can laugh at all your friends with their $10,000 homelab investment while you’re getting all the same goodness on commodity hardware :)

Also check out his Youtube channel for videos about libvirt, for example this video. After you got the basics down the official documentation is a good resource to read about the details.

You have a couple of choices to work with libvirt but I enjoy working with virsh a libvirt command line tool. I work with VMs through ssh or through virsh console <name-of-VM>. You could use them with a graphical interface but for this usecase (and all others tbf ;)) I find that inconvenient as we will only be using applications without GUI’s.

My image of choice is Alpine: its lightweight i.e. it has versions available with the bare minimum pre-installed. You can pick your release here. I picked a version that is called “virt” which optimized for virtual machines, I don’t know what that means, but I like it.

This is the commands I used to create the VMs:

virt-install

--name alpine-network-test

--ram 2048

--disk path=/var/lib/libvirt/images/alpine-network-test.qcow2,size=8

--vcpus 2

--os-type linux

--os-variant generic

--console pty,target_type=serial

--cdrom ./alpine-virt-3.14.2-x86_64.iso

If you are satisfied with one VM you created you can clone it with:

virt-clone --original alpine-network-test --name alpine-network-test-2 --auto-clone

To create new VM that is exactly the same, but with a different name.

Some useful commands:

virsh start <name-of-your-VM>: Starts your VMvirsh destroy <name-of-your-VM>: Stops your VMvirsh console <name-of-your-VM>: Get a shell to your VMvirsh list --all: Lists your VMsvirsh net-list --all: Lists all networks that libvirt created

Setup the bridge networks

Out of the box, all the VMs you have created will be on a network named “default” that is created and maintained by libvirt. The super nice thing about this is, is that all your VMs will have ip addresses and have access to the internet, because libvirt will use a DCHP service called dnsmasq and all your VMs will have access to the internet because libvirt will add the appropriate firewall rules with iptables. Also a DNS will be configured for you. VMs on the default network will not be able to communicate with each other by default. Because we are doing something more custom, and we want our VMs to be able to communicate to each other, we are going to setup networks of our own.

Note In this phase your VM will surely have an internet connection. Now is a great time to install all the software you think you will need. If you want to follow along your VMs will need: nftables and conntrack and ncat (any flavour of ncat will probably do).

We are going to create bridge networks with netplan. With netplan you can configure your own networks in yaml files, and they will be created upon boot. Pretty nice. As the backend for netplan I am using networkd (instead of NetworkManager). According to the site you can also use NetworkManager as the backend.

I recently switched from NetworkManager to networkd and I thought it would be painful, but it was not painful at all. Install networkd according to instructions. Start/enable the networkd service with systemctl. I connect to Wifi networks with iwd using the iwctl command line tool.

These are the two yaml file I used to define the two bridge network:

network:

version: 2

renderer: networkd

ethernets:

enp0s3:

dhcp4: false

dhcp6: false

bridges:

br0:

interfaces: [enp0s3]

addresses: [192.168.111.1/24]

mtu: 1500

nameservers:

addresses: [8.8.8.8]

parameters:

stp: true

forward-delay: 4

dhcp4: no

dhcp6: no

network:

version: 2

renderer: networkd

ethernets:

enp0s4:

dhcp4: false

dhcp6: false

bridges:

br1:

interfaces: [enp0s4]

addresses: [192.168.222.1/24]

mtu: 1500

nameservers:

addresses: [8.8.8.8]

parameters:

stp: true

forward-delay: 4

dhcp4: no

dhcp6: no

A bridge network is a virtual switch that you can virtually plug VMs into. These 2 yamls create 2 bridge interfaces: br0 and br1.

br0 will have ip address 192.168.111.1 and br1 will have ip address 192.168.222.1. I have not checked out netplan in great detail, so maybe you could do this a lot simpler. You can check their some other examples here.

These yamls files you can put in /etc/netplan and they will be processed upon boot. Or you can apply them with netplan apply <path-to-yaml>.

Now you need to configure the VMs that you created with libvirt to use these networks, instead of the default network. You can do that with:

virsh edit <name-of-VM>. You will be dropped into your default editor where you can change the settings of your VM that are stored in an xml file. Change the interface type to this:

<interface type='bridge'>

<mac address='52:54:00:a1:1d:6d'/> <!-- Choose a unique mac address -->

<source bridge='br1'/> <!-- Change this to the bridge that your VM should use -->

<model type='e1000'/>

<address type='pci' domain='0x0000' bus='0x00' slot='0x03' function='0x0'/>

</interface>

You need to assign 2 of your VMs to br0 and 2 to br1.

First steps in configuring networking on the VM

We are going to configure a lot of networking stuff. Creating the whole setup at once might be a little too much, therefore, in this section we are going to configure 1 VM to use the bridge network br0, and make it so it has access to the internet. After this, you will probably appreciate all the things that libvirt is doing for you by default ;).

When you log into one of your VMs with virsh console <name-of-VM>. You will have no access to the internet, your VM will not have an ip address, DNS won’t be configured and your host machine will not transfer packets from your VM to the internet.

First make sure that packet forwarding is turned on your host machine do: echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward. You can read more about it here. If you don’t turn this on, packets that are not meant for your machine will be dropped.

On the VMs you should also configure a DNS server they can use to resolve domain names, I used the DNS provided by google located at 8.8.8.8. Changing the file /etc/resolv.conf to contain the lines:

nameserver 8.8.8.8

nameserver 8.8.4.4

Does the trick. Whenever you VM needs to resolve a domain name, it will first try 8.8.8.8 and will use 8.8.4.4 as a backup.

The next step will be to configure an ip address for your VM. You can do that with iproute2. Check the status of current status of your machine with ip a. You can configure an ip address with:

ip address add 192.168.111.100/24 dev eth0

The output of ip a should look something like this:

2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP qlen 1000

link/ether 52:54:00:14:fe:ff brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 192.168.111.100/24 scope global eth0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::5054:ff:fe14:feff/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

The next thing we should do is to change the routes on the VM. You can check the known routes with ip route:

192.168.111.0/24 dev eth0 scope link src 192.168.111.100

This means your VM now knows how to reach destinations on the network 192.168.111.0/24. But in order to reach outside the network, we need to add a default route.

This default route will be the default route for all packets not destined for other known networks. To add the default route do ip route add default via 192.168.111.1 dev eth0. The output of ip route will be:

default via 192.168.111.1 dev eth0

192.168.111.0/24 dev eth0 scope link src 192.168.111.100

192.168.111.1 Is the ip address of br0 located on our host machine. A packet not destined for 192.168.111.0/24 will now go to 192.168.111.1. The routing table on your host machine will determine where the packet should go next. Check the routing on your host machine also with ip route.

Now for the last step, the host machine needs to be configured as a router. You can do that by changing your firewall settings with nftables with this config:

flush ruleset

table inet filter {

chain input {

type filter hook input priority filter; policy accept;

}

chain forward {

type filter hook forward priority filter; policy accept;

}

chain output {

type filter hook output priority filter; policy accept;

}

}

table inet nat {

chain postrouting {

type nat hook postrouting priority srcnat; policy accept;

ip saddr 192.168.111.0/24 counter masquerade

ip saddr 192.168.222.0/24 counter masquerade

}

}

This “firewall” has no filter rules, it will accept anything. Packets not meant for the host machine will be processed by postrouting.

The line ip saddr 192.168.111.0/24 counter masquerade says, if the source ip is any ip from the network 192.168.111.0/24, change it to the source address of the outgoing interface (meaning, make it seem as that packet came from the host). This is needed so the NAT device from your ISP thinks it is the host machine is sending the packets. In my case, without this step, packets were not processed by my NAT device. You can apply this “firewall” with nft -f <path-to-file>.

Now you should be able to curl, ping, download packages, etc.

Lets recap what we have done:

- Configured packet forwarding

- Configured a nameserver

- Configured the ip address

- Configured the ip routes

- Configured the host machine to be a router

Graphically we have made this:

Disclaimer: You can probably do this more efficient, but this is a very specific setup for learning purposes anyway, so it does not matter.

Simulate 2 clients behind NAT devices

We can expand upon the steps in the previous paragraph to create the setup so we can perform the hole punching we are after 2 clients behind NAT devices.

This is the setup we are going to create:

Start the 4 VMs you have created. I assumed you have configured 2 VM to be using br0 and 2 br1.

Assign the VM ip addresses and configure the routes

First we are going to give all the VM ip addresses and routes.

- On the NAT A VM run:

ip address add 192.168.111.101/24 dev eth0

ip route add default via 192.168.111.1 dev eth0

Make sure to turn on packet forwarding (echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward)

- On the NAT B VM run:

ip address add 192.168.222.101/24 dev eth0

ip route add default via 192.168.222.1 dev eth0

Make sure to turn on packet forwarding (echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward)

- On the client A VM run:

ip address add 192.168.111.100/24 dev eth0

ip route add default via 192.168.111.101 dev eth0

ip route del 192.168.111.0/24 dev eth0 # Upon assigning an ip in the first command this route is automatically created, delete this route manually, we want all traffic to go through our NAT VM

- On the client B VM run:

ip address add 192.168.222.100/24 dev eth0

ip route add default via 192.168.222.101 dev eth0

ip route del 192.168.222.0/24 dev eth0

Configure firewalls for the clients

Next we are going to configure the firewalls on the client VMs. On the client A and B VMs apply the following very simple firewall:

flush ruleset

table ip filter {

chain input {

type filter hook input priority 0; policy drop;

ct state invalid counter drop comment "early drop invalid packets, if connection tracking state is invalid"

ct state {established, related} counter accept comment "accept all connections related to connections made by us"

iif lo accept comment "accept loopback"

iif != lo ip daddr 127.0.0.1/8 counter drop comment "drop connections to loopback not coming from loopback"

tcp dport 22 counter accept comment "accept SSH"

counter comment "count dropped packets"

}

chain forward {

type filter hook forward priority 0; policy drop;

counter comment "count dropped packets"

}

chain output {

type filter hook output priority 0; policy accept;

counter comment "count accepted packets"

}

}

You can apply this firewall with nft -f <name-of-the-file>. So how does this work. Whenever a packets enters an interface it is processed by netfilter in the linux kernel. Depending on the packet it traverses a set of chains, and in each chain you can define a set of rules specifying what should happen to the packet. I highly recommand you check out the packet flow diagram in the nftables documentation, it is really helpful. It will give you an idea in what order packets will traverse different chains.

So lets take this firewall as an example, I defined the table “filter” containing chains that work on all packets from the “ip” family (IPv4). In this table I defined a chain called “input” and its of type filter with the input hook. This means, all IPv4 packets that are destined for the local machine, will be processed by this chain. If no rule is triggerd, the packet will be dropped (policy drop). If the connection state is invalid (whatever this means) the packet will be dropped. If the connection state is established or related, the packet will be accepted. If there is tcp traffic on port 22 it will be accepted. If no rule was triggered, the packet will be dropped.

The counter statement is very handy, it creates a counter that counts packets and bytes. You can do nft list ruleset which prints out the current rules that are active, and it also shows the updated counters. The counters will show you the number of packets and bytes that the rule triggered, which is very useful to see if your rules are working. For example if you are trying to connect through ssh, but you see that the ssh counter remains 0. You know your tcp packets on port 22 are not being triggered by the rule.

Configure the router VMs

On the NAT A and B VMs apply the following nftable rules:

flush ruleset

table inet filter {

chain input {

type filter hook input priority 0; policy drop;

ct state invalid counter drop

ct state {established, related} counter

counter comment "count dropped packets"

}

chain forward {

type filter hook forward priority 0; policy drop;

oif eth0 ct state invalid counter drop

oif eth0 ct state {new, established, related} counter accept

counter comment "count dropped packets"

}

chain output {

type filter hook output priority 0; policy accept;

}

}

table inet nat {

chain postrouting {

type nat hook postrouting priority srcnat;

oifname "eth0" counter masquerade comment "this is where the NAT happens"

}

chain prerouting {

type nat hook prerouting priority -100; policy accept;

# depending on what router VM change the ip address: either 192.168.222.100 or192.168.111.100

tcp dport { 22 } counter dnat ip to 192.168.222.100

}

}

Lets break this down (its very helpful to check the packet flow).

Whenever a packet arrives at an interface it is processed by the prerouting chain: all packets are accepted, whenever a tcp packet arrives on port 22

the destination address of that packet is changed to 192.168.222.100 (this is port forwarding, so ssh connection attempts do reach the client).

If a packet is not meant for a local process it goes to the forward chain, to be forwarded to the next location.

In the forward chain packets are accepted if the output interface is “eth0” and if the connection state is new, established or related.

Afer the forward chain packets will go to the postrouting chain.

If the output interface is “eth0”, I quote, the source address is automagically set to the ip of the output interface.

This is where the actual network address is translated.

Try holepunching!

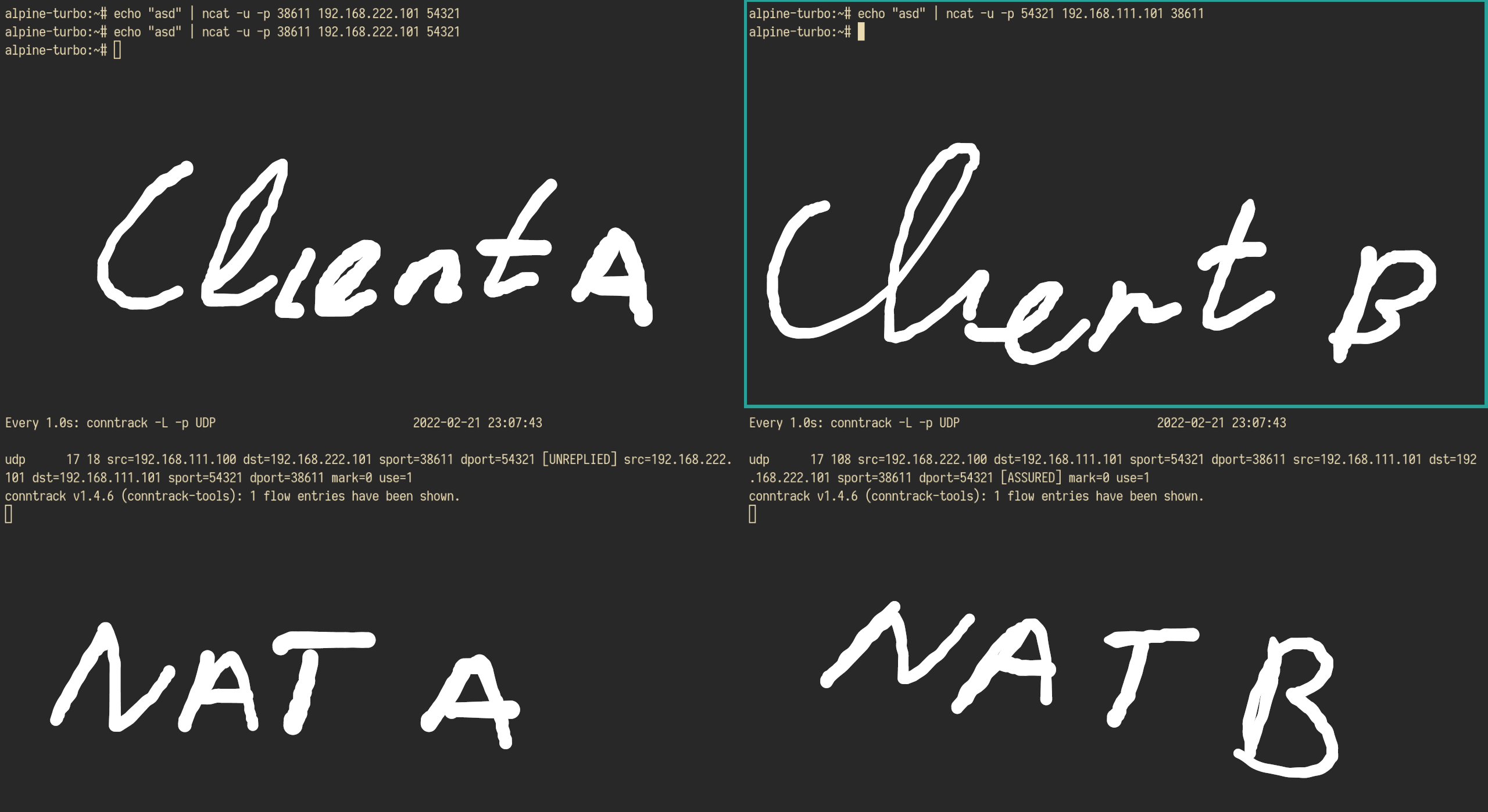

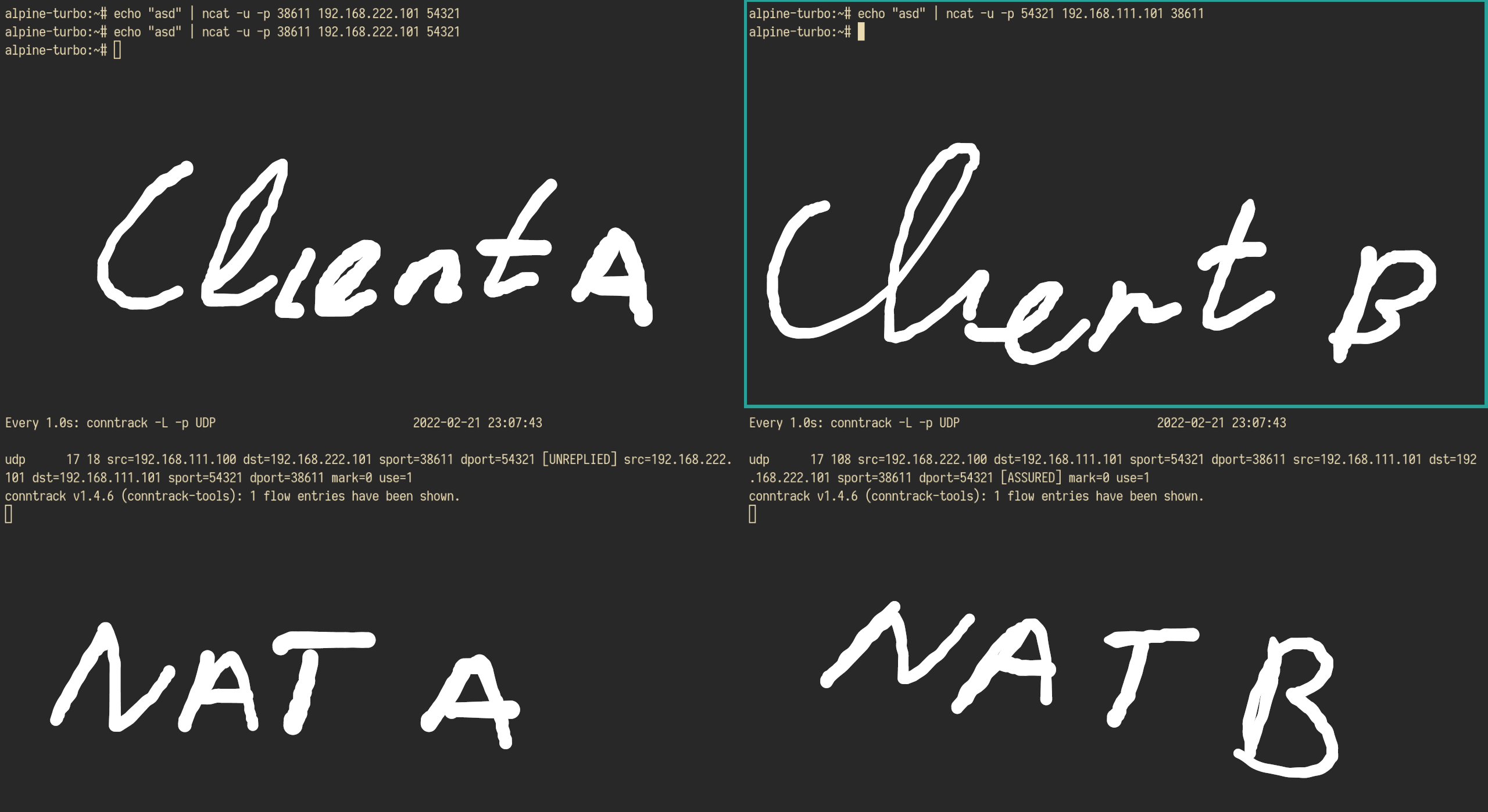

With these configurations in place it is time to holepunch! Now you can hole punch just like in Engineer Mans video.

This is an example of UDP holepunching. You can send UPD packets with ncat and control the source port numbers.

Do not forget to turn off the firewall on your host machine nft flush ruleset. On reboot your firewall will be back. And turn on packet forwarding.

To track the connections table on the NAT VM. I run the command watch -n 1 conntrack watch -n 1 conntrack -L -p UDP.

You can see the hole punching happening! And you can use it to diagnose when something is wrong.

This to do with this setup:

- Now you can tryout different NAT scenario’s check the nftables documentation!

- You can tryout TCP holepunching.

- You can use this as a simulation setup to try out communication over NAT.

- You can experiment with

nftables - Tryout firewall settings

- Install

tsharkand inspect your network traffic